http://www.pobonline.com/articles/88431-the-quintessential-surveyor

Home » The Quintessential Surveyor

The

Quintessential Surveyor

Students examine the work of Henry David Thoreau, writer and surveyor.

Surveyors are often found tucked away in the quiet corners of history. Many

figures that loom larger than life today once claimed surveying as a

profession. The art of measurement, when practiced correctly, is as much

philosophy as science in my view. A.C. Mulford, in his classic treatise

“Boundaries and Landmarks”1 described the attributes of a true surveyor: “Yet it

seems to me that to a man of active mind and high ideals the profession is

singularly suited… It is a profession for men who believe that a man is

measured by his work, not by his purse…”

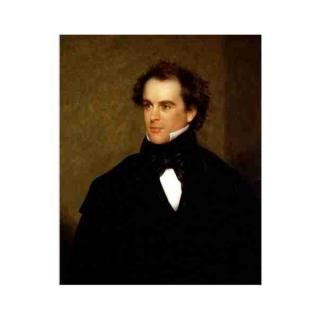

Writer, philosopher and

surveyor Henry David Thoreau was such a man. To say Thoreau’s mind was active

would be an understatement. His interests were broad and he spoke with

authority on many subjects. Thoreau was never satisfied with the status quo; he

was the type of person who refused to take “yes” for an answer. Thoreau’s view

of the role played by one’s occupation was simple. “Do not hire a man who does

your work for money, but him who does it for love of it…”2

Thoreau is best known for his literary works such as

“Walden” and “Civil Disobedience.” His contemporaries often judged him as

eccentric and a recluse. Although Thoreau’s literary work wasn’t fully

appreciated until the early 20th century, his work as a surveyor was well

thought of during his lifetime. Soon after Thoreau’s death in 1862, his friend

and mentor, Ralph Waldo Emerson, another acclaimed author of the time, wrote a

biographical essay in which he stated: “He [Thoreau] had a natural skill for

mensuration, growing out of his mathematical knowledge… his accuracy and skill

in this work [surveying] were readily appreciated, and he found all the

employment he wanted.”6 History and surveying go hand in hand. The profession

requires each surveyor to “follow in the footsteps” of those who have gone

before. It is for this very reason the study of our predecessors, which is

often neglected, is so important.

In the Footsteps of Thoreau

On May

6, 2002, some of my surveying students from Cleveland State Community College

and East Tennessee State University and I traveled to Concord, Mass., to study

Thoreau and his surveys. To prepare for the trip, the students focused on the

survey Thoreau did for Emerson during the winter of 1848. This is the property

where Thoreau lived while writing much of “Walden.” Thoreau’s cabin and pond

are on the south end of the property and the bean field, as described in

“Walden” is to the north. The cabin is gone now and the bean field is wooded.

The cabin was last seen as part of a hog pen for a local farmer.3

The students also

studied Thoreau’s field notes as published in “Transcendental Climate” by

Kenneth W. Cameron in 1963. The three-volume set contains facsimiles of the

journals and notes of well-known writers during the transcendental movement of

the 1800s. Reviewing Thoreau’s notes gave some insight as to why his work was

so highly regarded. Thoreau was a Harvard graduate and was an excellent

mathematician. He often conducted coordinate geometry, sans calculator, in the

margins of his field notes. Thoreau also thoroughly documented his research,

stating the source and date of the original survey. He took great care in

determining the magnetic declination for his surveys. It appeared he often

checked his declination using Polaris at elongation several times during the

course of many of his surveys. A handbill he distributed stated his surveys

were easily retraced due to his careful determination of magnetic declination.

Thoreau carefully described each corner he set in his field notes. It’s obvious

he understood the importance of preserving evidence. In R.B. Buckers book “Land

Surveyors Review Manual”4 he described the importance of preserving evidence this

way:

“One of the highest levels of professional responsibility

of a licensed land surveyor is demonstrated by his or her willingness to take

measures to preserve and perpetuate evidence of corner locations. That, in

fact, may be the primary reflection of professionalism.”

Instructor

Barry Savage (center) talks with Bradley Dean , PhD (right) by Walden Pond

while student Dave Sheely is hard at work. Thoreau's Cove can be seen in the

background.

On the

morning of May 10 we loaded the van and headed north. We arrived at the Thoreau

Institute around 1 a.m. on May 12. The following morning I let the guys sleep

in while I walked the site with Bradley Dean, PhD. Dean is a Thoreau scholar at

the Thoreau Institute at Walden Woods. I had contacted the institute in the

fall of 2001 for information regarding Thoreau’s surveys for a series of

lectures I was writing. One thing led to another and Dean invited us to the

institute. Our reason for going was twofold. It was a rare opportunity for my

students and Dean was to use the surveys in his writings and research. Visiting

the site with Dean was a unique experience. He knows Thoreau’s life and writings

very well so he pointed out subtle details I would have otherwise missed. Later

when I pointed out these tidbits to the students, I stressed the

often-overlooked responsibility of a surveyor to carefully measure, document

and describe such detail for future generations. Mulford put it this way: “…in

the hands of the Surveyor, to an exceptional degree, lie the honor of

generations past and the welfare of the generations to come; in his keeping is

the Doomsday Book of his community…”5 Following my initial site visit I decided to split the

students into two crews. One crew was to concentrate on the pond and cabin

site, the other crew focused on the bean field.

Once at the site we

divided into crews. Both crews used a Topcon GTS-223 total station (Topcon, Pleasanton,

Calif.) and HP48 data collectors (Hewlett Packard, Palo Alto, Calif.) with TDS

Survey Pro software (Tripod Data Systems, Corvallis, Ore.). The first crew

started at the south end of the Emerson lot. The second crew went to the north

end, in the area Dean believes to be the bean field described in “Walden.” The

southern crew began by locating two split stones supposedly set as markers by

Thoreau. His plat of 1848 shows 552.54' between the stones. The crew found the

distance to be 552.70', a little less than a quarter of a link. The crew used

this line as a base to calculate the likely positions of other markers.

Although no more monumentation was found, Thoreau’s drawings did show many

natural features, especially near the pond he so dearly loved. The distance

from the split stone to the water’s edge was 303.7' according to Thoreau’s

drawing. When the south crew got to the pond and did a stakeout to look for the

corner near the pond, the position fell exactly at the water’s edge, just as

Thoreau’s 1848 plat shows.

Students

(left to right): Nick Roberts, Tyson Olinger, Seth Klien, Dave Sheely, Zac

Morgan, Josh Morgan and instructor Barry Savage, PLS, on the shore of Walden

Pond.

The

crew to the north found Thoreau’s survey to be quite accurate as well. Thoreau

carefully describes the bean field in “Walden” by giving several measurements.

The bean rows were all described as being 15 rods in length. Judging from the

topography of the area it would appear this is an accurate measurement. There

were so many rows that if placed end to end they would total seven miles. Based

on writings in Thoreau’s journals the rows were placed three feet apart. It was

in Thoreau’s very nature to begin describing any place he wrote about by giving

dimensions first. Emerson once wrote that Thoreau had a “habit of ascertaining

the measures and distances of objects which interested him, the size of trees,

the depth and extent of ponds and rivers, the height of mountains, and the

air-line distance of his favorite summits…”6

The dimensions of the

bean field were just as Thoreau described, with only one discrepancy. The

dimensions for the field placed a small portion across the current roadway.

During our short trip, we didn’t have time to research the location of the road

as it existed in Thoreau’s day. The northern crew also located two sites known

as the “Zilpha cellar” and the “Whelan cellar.” Zilpha was a runaway slave who

lived near the bean field in the early 19th century. During the war of 1812

British troops burnt her home. Upon returning from work and finding her home

gone, she wandered off in despair and was never seen again. The Whelan site was

an area near the middle of the bean field. The Whelan family moved Thoreau’s

cabin to this site after he left the pond. They lived there until one night

during a snowstorm. Mr. Whelan had too much to drink and left his family, never

to return. The last known residents of the cabin were pigs, after parts of the

structure were used to construct a pen.

Surveying Truth

I wanted

the students to learn more than the mechanics of Thoreau’s work. I wanted them

to understand the vital roles integrity, truth and thought play in becoming a

surveyor. Emerson once described Thoreau as “a speaker and actor of the

truth&mdas;born such—and was ever running into dramatic situations from

this cause.” In Thoreau’s work “Life Without Principle” he writes: “As far as

my own business, even that kind of surveying which I do with most satisfaction

my employers do not want... When I observe there are different ways of

surveying, my employer commonly asks which way will give him the most land, not

which is most correct.” This is a dilemma every surveyor has faced. It is only

a dilemma when a surveyor forgets his or her primary role to tell the truth,

the entire truth; even if it’s not the truth our clients want to hear. Emerson

was correct when he described Thoreau’s dedication to truth as a catalyst for

confrontation. To a surveyor, always telling the truth has two universal

outcomes. One is a good night’s sleep; the other is the guarantee that half the

people he/she encounters will dislike the surveyor and his/her work.

It’s no secret that

over the past 75 years surveying has lost much of its former status as a

profession. Any surveying magazine you pick up today will most likely have an

article or two on how to improve our image in the public eye. I believe it is

important to study and understand those surveyors who came before us and had a

positive impact on society. Thoreau isn’t remembered for his surveying. He is

remembered as a person of thought and integrity. This might be a good place for

all of us to start.

References

1 Mulford, A.C. 1912. Boundaries and Landmarks New York: D.

Van Nostrand Company, 89.

2 Thoreau, Henry David. 1863. Life without principle. The

Atlantic Monthly (October).

3 Thoreau’s plat of this survey can be viewed at the

website for the Concord Free Public Library, www.concordnet.org/library and is

survey number 31a.

4 Buckner, R.B. 1991. Land Surveyors Review Manual. Rancho

Cordova: Landmark Enterprises, 325.

5 Mulford, Boundaries and Landmarks, 89.

6 Emerson, Ralph Waldo. 1862. Thoreau – Part 1: A

biographical essay. The Atlantic Monthly (August).