Providing a bully pulpit, a perch, a roof, a soap box for fiddlers, Quakers, Seekers, roosters, malcontents, true radicals, free thinkers or anyone with a beating heart and a working mind. In the spirit of Thoreau's chanticleer. "I do not propose to write an ode to dejection, but to brag as lustily as chanticleer in the morning, standing on his roost, if only to wake my neighbors up."

Sunday, April 30, 2017

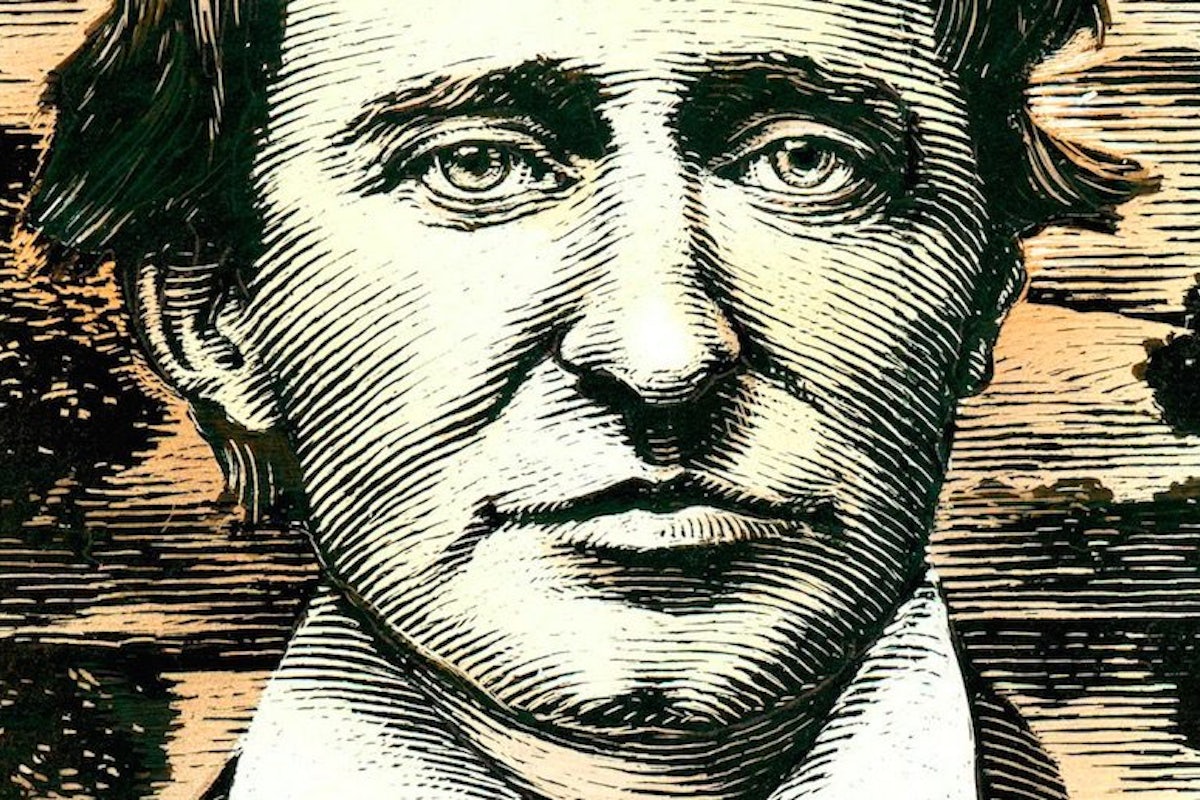

100 REFLECTIONS: The Sages of Concord #21

Thoreau made this trip to Montreal through Burlington, VT one hundred years To The Day before I was born. I lived in Burlington for nearly 20 years!

"You are in the midst of the Green Mountains. A few more elevated blue peaks are seen from the neighborhood of Mount Holly, perhaps Killington Peak is one. Sometimes, as on the Western rail-road, you are whirled over mountainous embankments . . . All the hills blush. I think that autumn must be the best season to journey over even the Green Mountains. You frequently exclaim to yourself, What red maples! "

Summit Cut, Killington, Vermont

I FEAR THAT I have not got much to say about Canada, not having seen much; what I got by going to Canada was a cold. I left Concord, Massachusetts, Wednesday morning Sep. 25th 1850, for Quebec. Fare seven dollars there and back; distance from Boston five hundred and ten miles; being obliged to leave Montreal on the return as soon as Friday Oct. 4th, or within ten days. I will not stop to tell the reader the names of my fellow travellers; there were said to be fifteen hundred of them. I wished only to be set down in Canada, and take one honest walk there, as I might in Concord woods for an afternoon.

"You are in the midst of the Green Mountains. A few more elevated blue peaks are seen from the neighborhood of Mount Holly, perhaps Killington Peak is one. Sometimes, as on the Western rail-road, you are whirled over mountainous embankments . . . All the hills blush. I think that autumn must be the best season to journey over even the Green Mountains. You frequently exclaim to yourself, What red maples! "

Summit Cut, Killington, Vermont

I FEAR THAT I have not got much to say about Canada, not having seen much; what I got by going to Canada was a cold. I left Concord, Massachusetts, Wednesday morning Sep. 25th 1850, for Quebec. Fare seven dollars there and back; distance from Boston five hundred and ten miles; being obliged to leave Montreal on the return as soon as Friday Oct. 4th, or within ten days. I will not stop to tell the reader the names of my fellow travellers; there were said to be fifteen hundred of them. I wished only to be set down in Canada, and take one honest walk there, as I might in Concord woods for an afternoon.

[2] . . .In Ludlow, Mount Holly, and beyond, there is interesting mountain scenery, not rugged and stupendous, but such as you could easily ramble over, long narrow mountain vales through which to see the horizon. You are in the midst of the Green Mountains. A few more elevated blue peaks are seen from the neighborhood of Mount Holly, perhaps Killington Peak is one. Sometimes, as on the Western rail-road, you are whirled over mountainous embankments, from which the scared horses in the valleys appear diminished to hounds. All the hills blush. I think that autumn must be the best season to journey over even the Green Mountains. You frequently exclaim to yourself, What red maples! The sugar-maple is not so red. You see some of the latter with rosy spots or cheeks only, blushing on one side like fruit, while all the rest of the tree is green, proving either some partiality in the light or frosts, or some prematurity in particular branches. Tall and slender ash trees whose foliage is turned to a dark mulberry color, are frequent. The butter-nut which is a remarkably spreading tree, is turned completely yellow, thus proving its relation to the hickories. I was also struck by the bright yellow tints of the yellow-birch. The sugar-maple is remarkable for its clean ankle. The groves of these trees looked like vast forest sheds, their branches stopping short at a uniform height, four or five feet from the ground, like eaves, as if they had been trimmed by art, so that you could look under and through the whole grove with its leafy canopy, as under a tent whose curtain is raised.

[4] As you approach Lake Champlain you begin to see the New York mountains. The first view of the lake at Vergennes is impressive, but rather from association than from any peculiarity in the scenery. It lies there so small (not appearing in that proportion to the width of the state that it does on the map,) but beautifully quiet, like a picture of the Lake of Lucerne on a music box, where you trace the name of Lucerne among the foliage; far more ideal than ever it looked on the map. It does not say, "Here I am, Lake Champlain," as the conductor might for it, but having studied the geography thirty years, you crossed over a hill one afternoon and beheld it. But it is only a glimpse that you get here. At Burlington you rush to a wharf and go on board a steamboat two hundred and thirty-two miles from Boston. We left Concord at twenty minutes before eight in the morning, and were in Burlington about six at night, but too late to see the lake. We got our first fair view of the lake at dawn, just before reaching Plattsburg, and saw blue ranges of mountains on either hand, in New York and in Vermont, the former especially grand. A few white schooners like gulls were seen in the distance, for it is not waste and solitary like a lake in Tartary, but it was such a view as leaves not much to be said; indeed I have postponed Lake Champlain to another day.

[5] The oldest reference to these waters that I have met with is in the account of Cartier's (5) discovery and exploration of the St. Lawrence in 1535. Samuel Champlain(6) actually discovered and paddled up the lake in July, 1609, eleven years before the settlement of Plymouth, accompanying a war party of the Canadian Indians against the Iroquois. He describes the islands in it as not inhabited although they are pleasant, on account of the continual wars of the Indians, in consequence of which they withdraw from the rivers and lakes into the depths of the land, that they may not be surprised. "Continuing our course", says he "in this lake, on the western side, viewing the country, I saw on the eastern side very high mountains, where there was snow on the summit. I inquired of the savages if those places were inhabited. They replied that they were, and that they were Hiroquois, and that in those places there were beautiful valleys and plains fertile in corn, such as I have eaten in this country, with an infinity of other fruits." This is the earliest account of what is now Vermont.

from http://thoreau.eserver.org/Canada1.html

Friday, April 28, 2017

100 REFLECTIONS: The Sages of Concord #20

"And he was a poor student

who once lost a hound, a bay horse, and a turtle dove and spent his whole life

searching for them; a moral philosopher; a patriot and a dissident; a prose

stylist so exquisite Dickinson, Frost, Tolstoy, Proust, Carson, Robinson, Dillard,

and Schulz admired his sentences; who tried his best to live and write

deliberately, and succeeded better than most; an epic perambulist and a

committed abolitionist; a sufferer of tuberculosis from his youth to his death

who nevertheless ascended Mount Katahdin; . . ."

A beutifully written rebuttal to a well-written teardown of Thoreau. I recommend both because, like Thoreau, they force you to see things differently and more clearly.

https://newrepublic.com/article/123162/everybody-hates-henry-david-thoreauThursday, April 27, 2017

MINDS ON FIRE: The Sages of Concord #19

"By virtue of its openness to science . . . transcendentalism avoids divorcing itself from the mainstream of modern science and technology. But it affirms that ”not he is great who can alter matter, but who can alter my state of mind.” Some say that modern liberalism is without a soul . . . It is the ambition, if it has not yet been the fate, of transcendentalism to provide a soul for modern liberalism and thereby to enlarge the possibilities of modern life.”

" Transcendentalism

did not change American life, but it did change – and continues to change—individual

American lives. Transcendentalism was not only a literary philosophical and

religious movement; it was also, inescapably, a social and political movement

as well. . . . Thoreau could say ”the purest science is still biographical,”

or, as Emerson might have said, there is, finally, no science, there are only

scientists.

In

religion transcendentalism teaches that the religious spirit is a necessary aspect

of human nature . . In literature

transcendentalism holds that it is a built-in necessity of human nature to

express itself . . .The social imperative of transcendentalism

is twofold. It insists, first, that the well-being of the individual – of all

the individuals – is the basic purpose and the ultimate justification for all

social organizations and second that autonomous individuals cannot exist apart

from others. . . that the purpose of education is to facilitate the

self-development of each individual. The political trajectory of

transcendentalism begins in philosophical freedom and ends in democratic

individualism.

By virtue of its openness to science . . . transcendentalism avoids divorcing itself from

the mainstream of modern science and technology. But it affirms that ”not he is

great who can alter matter, but who can alter my state of mind.” Some say that

modern liberalism is without a soul . . . It is the ambition, if it has not yet

been the fate, of transcendentalism to provide a soul for modern liberalism and

thereby to enlarge the possibilities of modern life.”

from Emerson: Mind On Fire by Robert D. Richardson, Jr.

Wednesday, April 26, 2017

100 REFLECTIONS: The Sages of Concord #18

http://www.newenglandhistoricalsociety.com/two-loves-louisa-may-alcott/

Before Louisa May Alcott wrote Little Women, she wrote a book about a young girl named Sylvia in love with an intellectual like Ralph Waldo Emerson and a naturalist like Henry David Thoreau.

It was called Moods, and it wasn’t all that fictional.

Louisa May Alcott had an unrequited love for her schoolteacher Henry David Thoreau – and for her generous next-door neighbor, Ralph Waldo Emerson.

Thoreau, 16 years her senior, would not win wide acclaim as the author of Walden and Civil Disobedience until well after his death. He was recognized around town, though, as someone who marched to the beat of a very different drummer.

Emerson, nearly three decades older than Louisa May, had both fortune and fame as the leading Transcendentalist philosopher, lecturer, poet and essayist. He brought together the literary and philosophical community of Concord, Mass., where Louisa May spend much of her childhood. Emerson had inherited a large estate from his wife, Ellen Tucker, who died at 20, just two years into their marriage.

He supported Thoreau, promoting his work, hiring him for odd jobs and letting him live at his large house with his second wife and children. He gave and loaned money to Nathaniel Hawthorne and his wife Sophia Peabody. He bought houses for Bronson Alcott, the founder of alternative education and the father of Louisa May and her three sisters.

Alcott was an entertaining eccentric, a vegan before the word existed, and a poor provider for his family. Louisa May grew up poor in material things but rich in intellectual companionship.

Born on Nov. 29, 1832, she was a rambunctious, independent child. Susan Cheever describes her as ‘that hoping, dreaming girl with the long glossy hair.’

When she was about seven her father enrolled her in a school taught by Thoreau, then 23. Thoreau often took his students out of the classroom into the woods. He taught them about birds and flowers, gathering lichens, showing them a fox den and deer tracks, feeding a chipmunk from his hand.

Sometimes he took the children on his boat, the Musketaquid, and gave them lessons as they floated down the Sudbury and Assabet rivers. As they passed the battlefield where the American Revolution started, he explained how the farmers had defended themselves against the redcoats. Louisa recorded her vivid memories of those field trips in Moods.

Thoreau had love interests other than the smitten schoolgirl. Perhaps his lack of personal hygiene, his shabby clothes and terrible table manners put them off. Not Louisa. “Beneath the defects the Master’s eye saw the grand lines that were to serve as the model for the perfect man,” she wrote.

Louisa May’s crush on Thoreau competed with her interest in Emerson. Her family moved to a cottage next door to him. As a teenager, she often borrowed books from Emerson’s library and left wildflowers on his front step. He pretended he didn’t know where they came from.

Thoreau died in 1862, only 44 years old. By then, Louisa May Alcott was nearing 30, officially a spinster, after years of living in poverty. She had been working and writing potboilers, which brought in a little money, and volunteered as a Civil War nurse in Washington, D.C. There she fell ill and returned home to Concord in 1863.

Mourning Thoreau’s death while in the hospital, Louisa May had written a poem about him called Thoreau’s Flute. It was published in The Atlantic in the summer of 1863. It fell out of her papers and her father read it. The poem began:

We sighing said, "Our Pan is dead;

His pipe hangs mute beside the river;

Around it wistful sunbeams quiver,

But Music's airy voice is fled.

Spring came to us in guise forlorn;

The bluebird chants a requiem;

The willow-blossom waits for him;--

The Genius of the wood is gone.

His pipe hangs mute beside the river;

Around it wistful sunbeams quiver,

But Music's airy voice is fled.

Spring came to us in guise forlorn;

The bluebird chants a requiem;

The willow-blossom waits for him;--

The Genius of the wood is gone.

In 1869 Louisa achieved lasting literary fame with Little Women. Some say she based the character Laurie on Emerson … or was it Thoreau?

Louisa May Alcott died on March 6, 1888.

With thanks to American Bloomsbury by Susan Cheever. This story was updated from the 2014 version.

Tuesday, April 25, 2017

100 REFLECTIONS: The Sages of Concord # 17

I

do not prefer one religion or philosophy to another. I have no sympathy with

the bigotry and ignorance which make transient and partial and puerile

distinctions between one man’s faith or form of faith and another’s – as Christian

and heathen. I pray to be delivered fr5om narrowness, partiality, exaggeration,

bigotry. To the philosopher all sects, all nations, are alike. I like Brahma,

Hari, Buddha, the Great Spirit, as well as God.

Thoreau’s

Journal (ca. 1850)

Monday, April 24, 2017

100 REFLECTIONS: The Sages of Concord #16

I had the privilege of hearing Swami Satchidananda at the Riverside Church in NYC shortly before (after?) this photo at Woodstock was taken. He talked about how some bees dive into the honey and others like to sit on the rim of the honey jar and call the other bees over. I seem to be of the latter bent. (My way of bee-ing?) I also had the honor of driving Swami and Eido-Tai Shimano to an event in Brooklyn a few years later. I'm embarrassed to say that I nearly killed us all by driving too fast on the West Side Highway. No one said anything, I averted the stone wall, but Swami, who was riding shotgun, looked pretty shaken up.

Saturday, April 22, 2017

100 REFLECTIONS #15

‘

. . . Hardly a man takes a half hour’s nap after dinner, but when he wakes he

holds up his head and asks, “What’s the news?” as if the rest of mankind has

stood his sentinels. Some give directions to be waked every half hour,

doubtless for no other purpose; and then, to pay for it, they tell what they

have dreamed. After a night’s sleep, the news is indispensable as the

breakfast. “Pray tell me anything new that has happened to a man on

this globe” – and he reads it over his coffee and rolls, that a man has had his

eyes gouged out this morning on the Wachito River; never dreaming the while

that he lives in the dark unfathomed mammoth cave of this world, and has but

the rudiment of an eye himself.’

Walden, Where I Lived and What I Lived For

Friday, April 21, 2017

100 REFLECTIONS: The Sages of Concord #14

A Re-post from Ten Years Ago

Thursday,

March 8, 2007

I

just discovered this account by Ralph Waldo Emerson about Henry David Thoreau

(a hero

of

mine since the day I accidentally did my homework in High School). All I can

say is

"Hooray"

for the, then, president of Harvard! I laughed until I cried.

"On one occasion he went to the [Harvard] University Library to procure some books.

"On one occasion he went to the [Harvard] University Library to procure some books.

The

librarian refused to lend them. Mr. Thoreau repaired to the President, who

stated

to

him the rules and usages, which permitted the loan of books to resident

graduates,

to

clergymen who were alumni, and to some other residents within a circle of ten

miles

radius

from the College. Mr. Thoreau explained to the President that the railroad had

destroyed the old scale of distances, — that the library was useless, yes, and

President

and

College useless, on the terms of his rules,— that the one benefit he owed to

the

College

was its library, — that, at this moment, not only his want of books was

imperative,

but

he wanted a large number of books, and assured him that he, Thoreau, and not the

librarian, was the proper custodian of these. In short, the President found the

petitioner

so

formidable, and the rules getting to look so ridiculous, that he ended by

giving him a privilege which in his hands proved unlimited thereafter." -Ralph Waldo Emerson

I also just discovered this website: The Thoreau Reader: thoreau.eserver.org/default.html

I recommend a paragraph a day for sanity's sake.

I also just discovered this website: The Thoreau Reader: thoreau.eserver.org/default.html

I recommend a paragraph a day for sanity's sake.

Thoreau’s Harvard Library Charging List

http://library.harvard.edu/02042014-1336/henry-david-thoreau-library

Thursday, April 20, 2017

Wednesday, April 19, 2017

Tuesday, April 18, 2017

Monday, April 17, 2017

100 REFLECTIONS: The Sages of Concord #10

“I learned this, at least, by my experiment: that if one advances confidently in the direction of his dreams, and endeavors to live the life which he has imagined, he will meet with a success unexpected in common hours.”

Walden or

Life in the Woods

Sunday, April 16, 2017

100 REFLECTIONS: The Sages of Concord #9

PENANCE

I would fain say something, not so much

concerning the Chinese and Sandwich Islanders as you who read these pages, who

are said to live in New England; something about your condition, especially

your outward condition or circumstances in this world, in this town, what it

is, whether it is necessary that it be as bad as it is, whether it cannot be

improved as well as not. I have traveled a good deal in Concord; and

everywhere, in shops, in offices, and fields, the inhabitants appeared to me to

be doing penance in a thousand remarkable ways.

. . .The twelve labors of Hercules were trifling in comparison with

those which my neighbors have undertaken; for they were only twelve, and had an

end; but I could never see that these men slew or captured any monster or

finished any labor. They have no friend Iolaus to burn with a hot iron the root

of the hydra’s head, but as soon as the head is crushed, two spring up.

Saturday, April 15, 2017

100 REFLECTIONS: The Sages of Concord #8

He was a lucky fox that left his tail in a trap.

from Economy, Walden

from Economy, Walden

Thursday, April 13, 2017

100 REFLECTIONS: The Sages of Concord #7

THE NICK OF TIME

How many a man has dated a new era in his life from the reading of

a book!

Henry

David Thoreau Walden

This is neither brag nor

confession. I was a “C” student. I was

not very disciplined about doing my homework. When it came time to hand in our

assignments, it was fairly likely that I would not have it. If we were assigned

to read something I might have read it, I might not have. There was no

guarantee. I’m not a betting man but, if

I were, and you asked me to bet on whether I would have read a particular

assigned reading, I would bet not.

Fortunately, in one case, I would

have bet wrong. We had been assigned a very short reading from Henry David Thoreau’s

Walden. It was a section from the chapter “Where I Lived and What I

Lived For.” I was probably attracted to

the title. I was struggling with what I wanted to do with my life. I was in my

third year of High School. I was in my father’s kitchen. The TV may well have

been on in the next room or, perhaps the radio. I was seated at the table. I

opened my text book and read:

I

went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, … and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not

lived.

As Quakers would say, this spoke to

my condition.

I did not

wish to live what was not life,…I wanted to live deep and suck out all the

marrow of life, … to drive life into a corner, and reduce it to its lowest

terms, and, if it proved to be mean, why then to get the whole and genuine

meanness of it, …or if it were sublime, to know it by experience…

To suck

out all the marrow of life? To drive life into a corner? He had my attention.

… An honest

man has hardly need to count more than his ten fingers, or in extreme cases he

may add his ten toes, and lump the rest. Simplicity, simplicity, simplicity! I

say, let your affairs be as two or three, and not a hundred or a thousand; …such

are the clouds and storms and quicksands …that a man has to live, …by dead

reckoning, and he must be a great calculator indeed who succeeds. Simplify,

simplify. Instead of three meals a day, if it be necessary eat but one; instead

of a hundred dishes, five; and reduce other things in proportion.

Simplicity? I didn’t know what he

was talking about. And, I didn’t know why but it seemed to run counter to

everything I had been taught. It seemed like such a radical idea, I couldn’t

believe that they put it in a school textbook. Simplify? What about the messages

I had gleaned from TV, radio, friends, family, school: “Decide what you were

going to do for the rest of your life and sell your soul in order to accomplish

it?” What about “Acquire, acquire, acquire?” What about “Work, work, work to

make money, money, money so that you can buy, buy, buy?”

If Henry Thoreau had risen from the

dead and walked into my father’s kitchen and grabbed me by the throat, I don’t

know if I would have been as choked up as I was by these incredible words. No

matter that I didn’t understand most of them. They seemed to be in another

language but a language so beautiful and poignant that I had to learn it. I

would learn it. I needed to learn it.

******

from Lonely Road

Tuesday, April 11, 2017

100 Reflections: The Sages of Concord #6

from Slavery in Massachusetts by HD Thoreau

. . .The whole military force of the State is at the service of a Mr. Suttle, a slaveholder from Virginia, to enable him to catch a man whom he calls his property; but not a soldier is offered to save a citizen of Massachusetts from being kidnapped! Is this what all these soldiers, all this training, have been for these seventy-nine years past? Have they been trained merely to rob Mexico and carry back fugitive slaves to their masters?

Every humane and intelligent inhabitant of Concord, when he or she heard those bells and those cannons, thought not with pride of the events of the 19th of April, 1775, but with shame of the events of the 12th of April, 1851. But now we have half buried that old shame under a new one.

. . . I wish my countrymen to consider, that whatever the human law may be, neither an individual nor a nation can ever commit the least act of injustice against the obscurest individual without having to pay the penalty for it. A government which deliberately enacts injustice, and persists in it, will at length even become the laughing-stock of the world.

I hear a good deal said about trampling this law under foot. Why, one need not

go out of his way to do that. This law rises not to the level of the head or

the reason; its natural habitat is in the dirt. It was born and bred, and has

its life, only in the dust and mire, on a level with the feet; and he who walks

with freedom, and does not with Hindoo mercy avoid treading on every venomous

reptile, will inevitably tread on it, and so trample it under foot — and

Webster, its maker, with it, like

the dirt-bug and its ball.

The law will never make men free; it is men who have got to make the law free.

They are the lovers of law and order who observe the law when the government

breaks it.

Monday, April 10, 2017

100 REFLECTIONS: The Sages of Concord #5

“We would have every arbitrary barrier thrown down. We would

have every path laid open to woman as freely as to man.”

from “The Great Lawsuit: Man vs. Men, Woman vs. Women," by

American journalist, editor, and women's rights advocate Margaret Fuller. Originally

published in July 1843 in The Dial

magazine, which she edited with RW Emerson. Later published in book form

as Woman in the Nineteenth Century.

Saturday, April 8, 2017

100 Reflections: The Sages of Concord #4

To Want One Thing

“To live within limits. To want one thing. Or a few things very much and love them dearly. Cling to them, survey them from every angle. Become one with them - that is what makes the poet, the artist, the human being.”

Johann Wolfgang von GoetheGoethe's ideas were central to the thinking of Emerson, Fuller, Thoreau and other Transcendentalists.

Friday, April 7, 2017

HOW DOES IT BECOME YOU AND ME?: The Sages of Concord #3

How Does It Become You and Me?

" . . . a common and natural result of an undue respect for law is, that you may see a file of soldiers, colonel, captain, corporal, privates, powder monkeys and all, marching in admirable order over hill and dale to the wars, against their wills, aye, against their common sense and consciences, which makes it very steep marching indeed . . .They have no doubt that it is a damnable business in which they are concerned, they are all peaceably inclined. Now what are they, men at all? or small movable forts and magazines, at the service of some unscrupulous man in power? . . .

"How does it become a man to behave toward this American government to-day? I answer that he cannot, without disgrace, be associated with it . . ."

from "Resistance To Civil Government" (Civil Disobedience) by HD Thoreau

100 Reflections: The Sages of Concord #2

I

think that it is fair to say that discovering Henry David Thoreau’s writings

has had a major impact on my life. There has been hardly a week, hardly a day

since, when I have not thought about something Henry wrote.

Of

course, this is, in part, due to the tremendous influence his writings have had

on the world. Someone who influences Gandhi, King and Tolstoy has to influence

the rest of us in some way, whether or not we are aware of it. I remember

reading quotes of his on the subways and buses of Brooklyn and Manhattan. I saw

posters and heard songs about people who were traveling “to the beat of a

different drum.” I was assigned readings

from Walden in community college which I interpreted, rightly or

wrongly, as an encouragement to drop out. When tempted to beat myself up,

psychologically, for never having made it to Europe, I have always remembered

that Thoreau wrote, proudly, that he had “…travelled widely in Concord,” and

remembered, also, that I have traveled widely in New England and North America,

whether or not I have been able to muster the same depth of observation, musing

or recording of those travels.

I

see Thoreau’s influence as a major strand in the cord of my life; much as my thirty

year experience with Quakers has been a major strand. In fact, it’s altogether

possible that, if he had not planted the seeds of “simplicity, simplicity,” in

my high school brain, I might never have appreciated the witness of Friends. I

might not have even discovered them. I see both discoveries as among the great

blessings of my life.

Is

there another strand? I think there are several. But, looking back, I see a lot

of loneliness and a search for love and community.

And,

then, there is my father.

Prologue: from Lonely Road

******

ONE HUNDRED REFLECTIONS ON AND BY THE SAGES OF CONCORD

I awoke at 2 a.m. this morning aware that HD Thoreau’s 200th

birthday is approaching in (about) 100 days. Let’s post a reflection or two

every day in honor of the man and of his cohort who have so influenced and continue

to influence the American idea: The Sages

of Concord.

His dying

does not seem to have hurt him a bit.

Walt Whitman 'concluded that Thoreau was “one of the native

forces--stands for a fact, a movement, an upheaval: Thoreau belongs to America,

to the Transcendental, to the protesters . . . he was a force- he looms up bigger

and bigger: his dying does not seem to have hurt him a bit: every year has

added to his fame.”’

From

Henry Thoreau: A Life of the Mind by

Robert D. Richardson, Jr.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)